What is an engine oil analysis?

Engine oil analysis is a process that involves a sample of engine oil, whether virgin or used, and analyzing it for various properties and materials in order to monitor wear metals and contamination. By analyzing a sample of used engine oil, you can determine the wear rate, and overall service condition of an engine, along with spotting potential problems and imminent failure before it happens. This has become a critical tool in certain industries such as aviation, racing, and commercial shipping fleets where downtime due to engine failure can be costly and potentially dangerous.

How does an engine oil analysis work?

Oil analyses are offered by many companies, and accomplished by using spectrometry, which is generally defined as “the measurement of radiation intensity as a function of wavelength”. A spectral exam is done by injecting the oil sample into inductive coupled argon plasma, which is around 10,000° Celsius. The light generated from the complete combustion of the oil as it’s injected into the plasma is directed through a prism, and then broken up into different wavelengths and intensities. Those wavelengths are then collected on an aperture plate, sensed by a photomultiplier tube, and given as a digital readout on the computer’s display. Each element and their concentrations have their own unique wavelength and intensity which can be matched against a calibrated sample to give you an accurate readout of each element and their concentration.

What is a real world application for an engine oil analysis?

By knowing the amount of each elemental metal in the sample, you are able to narrow down and monitor wear patterns of specific components in an engine, such as bearings or valve stems. Not only can an analysis detect these elemental metals, they can also detect various types of contamination too. Insoluble matter (carbon, dirt, etc), fuel, or coolant can all be detected, and give you the ability to spot any abnormalities before they become a costly or dangerous problem. This allows industries to increase an engine’s service life, reduce repair bills, unscheduled down time, and potential catastrophic failures.

Interpreting and understanding an engine oil analysis report:

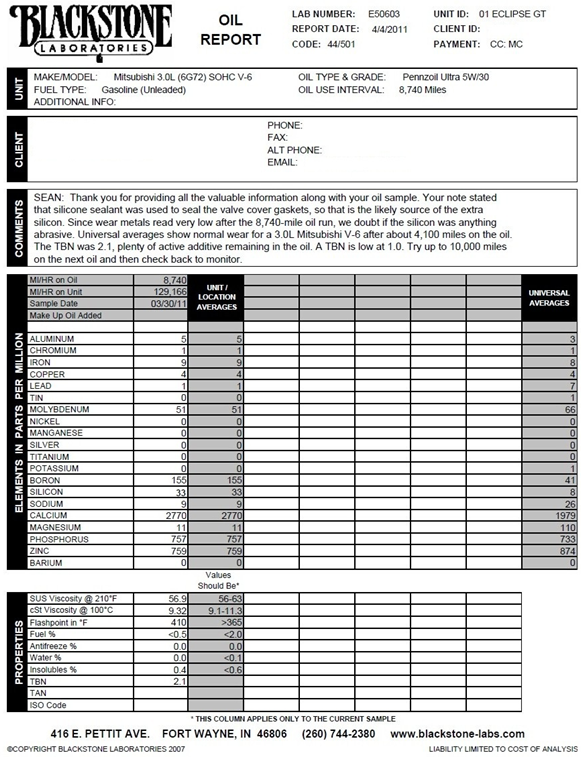

Below is a report given on a sample of used engine oil which I had analyzed from my personal vehicle, and the source each wear metal generally indicates inside of an engine.

Aluminum

Aluminum is most commonly from wear (scuffing) on piston skirts as they repeatedly travel along the length of a cylinder. Other sources often include aluminum engine blocks, certain types of bearings, and heat exchangers (oil coolers).

Chromium

The source of chromium wear metals are almost always from piston rings, which are used to form a tight seal between the moving piston and stationary cylinder wall. These rings have to reliably create a tight seal between the piston and the cylinder wall while travelling at up to 4,000+ feet per second and dealing with peak pressures of over 2,000 psi (136 Bar) depending on the engine design and usage.

Iron

This is the only wear metal that accurately and linearly increases with the length of time the oil has been in service. It has many sources inside of an engine, most commonly coming from cylinder liners, camshaft lobes, crankshaft journals, and oil pumps.

Copper

Copper is widely used due to its high ductility and thermal conductivity. It is mainly utilized in bushings and bearings such as: crankshaft journal bearings, connecting rod bearings, camshaft bushings, piston wrist pin bushings, thrust washers, and even heat exchangers (oil coolers).

Lead

Lead is a soft, sacrificial wear metal used on surfaces such as bearings. Lead based Babbitt alloys. Commonly found in main crankshaft journal bearings and contaminated fuels. Other sources include leaded fuels and gasoline octane improvers.

Tin

Commonly alloyed with Copper and Lead, it is typically found in crankshaft journal, connecting rod, and camshaft bearings, along with heat exchanger cores and thrust washers.

Molybdenum

This is most commonly used as an anti-wear/anti-scuff additive and has an effect commonly called “Moly plating” where over time, a thin and microscopic layer of Molybdenum tends to form between contact surfaces, thereby creating a lower coefficient of friction between the two parts. Concentration levels of Molybdenum vary greatly depending on the formulation of each specific oil brand, and viscosity.

Nickel

Though not very widely used anymore, Nickel can be found in certain alloys of steel for internal engine parts, and also is used as a coating on bearings.

Manganese

Manganese is sometimes used in certain steel alloys and has virtually no other uses in these applications.

Silver

Due to its exceptional thermal conductivity, it is occasionally implemented as a coating on bearings to help provide minimal friction. However, it is susceptible to corrosion from Zinc-based additives and is not commonly used in the U.S.

Titanium

Titanium is a newer, more environmentally friendly anti-wear additive being implemented due to more stringent emissions regulations, and is phasing out the older, more harmful phosphorous compounds such as ZDDP (Zinc dialkyldithiophosphate). ZDDP reduces the effectiveness of the catalysts in catalytic converters by creating a plating effect when combusted, and covering the catalyst while Titanium does not. Titanium chemically binds to wear surfaces creating a hard, Titanium based oxide layer which reduces friction, thereby reducing wear. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Potassium

Most commonly found if there is a coolant mixing with, and contaminating the engine oil.

Boron

Used as a corrosion inhibiter, anti-wear and anti-oxidant additive. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Silicon

A very common contaminant most often found in a very abrasive solid form, which causes increased metal wear numbers (especially Iron) in oil samples. . Its most common source is insufficient air filtration. However, in my oil analysis report it is actually harmless and due to leaching from a silicone sealant I used to seal a leaking valve cover gasket. Silicon concentrations in such cases as this will typically drop after each subsequent oil change

Sodium

This is most commonly used as a corrosion inhibiter additive, and occasionally can indicate a coolant leak into the oil. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Calcium

Used as a detergent and dispersant additive to maintain suspension of particulate matter, along with maintaining a reserve alkalinity. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Magnesium

Also used as a detergent and dispersant additive to maintain suspension of particulate matter, and occasionally used in certain alloys of steel. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Phosphorus

Used as an anti-wear, anti-oxidant, extreme pressure, and corrosion inhibitor additive. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Zinc

Another anti-wear, anti-oxidant, and corrosion inhibitor additive also commonly found in bearing alloys. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

Barium

A detergent which also acts as another corrosion and rust inhibitor used in some synthetic oils. Concentration levels vary greatly depending on oil brand.

SUS Viscosity @ 210°F

The Saybolt Universal Second (SUS) viscosity is the measurement of time that 60 cm3 of oil takes to flow through a calibrated tube at a controlled temperature (210°F in this case). Each weight of oil such as a 30 weight (5w30/10w30/etc) has an acceptable range to fall into to meet that grade. In this case of a used motor oil sample, it should fall between 56 and 63 SUS. It fell at 56.9, which is slightly less viscous than a virgin sample of this identical oil, which began at 58.3 SUS. That means the sample had a 2.4% viscosity loss over its service life due mainly to shearing and slight fuel dilution. Oils such as Castrol Edge 5w30 are on the thinner end of the 30 weight spectrum, and are on the borderline of being a “thick” 20 weight oil straight from the bottle.

cSt Viscosity @ 100°C

Viscosity at 100°C given in Centistokes. Less commonly used so there isn’t much to discuss here. Sorry folks.

Flashpoint in °F

This is the temperature at which the oil sample will start to combust in °F. Lower flashpoints tend to indicate a presence of fuel. The flashpoint of this sample was 410°F while a virgin sample of this identical oil began at 420°F, so the fuel content of this sample is actually quite low and well within the generally accepted ranges.

Fuel %

This is the amount of raw fuel content in your oil sample given as a percentage of total volume. Fuel dilution is common from cold starts with lots of idling (engine ECUs typically run rich on a cold idle) and short trips. This causes raw fuel to work past the piston rings and into your crankcase, which dilutes your oil and acts as a solvent, partially washing away the critical oil film and increasing wear between parts. This is why used motor oil, especially on older carbureted vehicles, sometimes smells strongly of gasoline.

Antifreeze %

Percentage of antifreeze found in the sample given as a percentage of total volume. Antifreeze will show up in an oil sample and indicate a coolant leak into the oil from such things as cracked engine blocks or cylinders heads, and leaking cylinder head gaskets.

Water %

Percentage of water found in sample given as a percentage of total volume. Moisture is common in short trip vehicles that don’t fully get the oil up to operating temperature long enough. It generally takes 10-15 minutes for the oil to get to this temperature, which is enough to start evaporating the moisture in the sample. The same goes for fuel in your sample too. An occasional long highway drive is good for your oil’s health.

Insolubles %

This is the amount of insoluble material in the oil sample given as a percentage of total volume. The most common insolubles are carbon from the combustion chamber, oxidation of the oil, and dirt that gets sucked in through the engine’s intake system. This is mostly what turns your oil darker the longer it has been in service. Higher insoluble percentages often indicate insufficient air and oil filtration.

TBN

The TBN (Total Base Number) is a lubricant’s reserve alkalinity measured in milligrams of potassium hydroxide, or calcium sulfonate per gram of oil. In more simple terms it is the amount of active additives remaining. This number is important because combustion byproducts tend to form acidic compounds and the TBN is the acid-neutralizing capacity of the lubricant. The TBN does not decrease linearly with the time it has been in use. Example: it could start out at a TBN of 10, drop to 5 after only 1,000 miles of use, and then stabilize around 3 for a majority of the remaining service life. A TBN of <1.0 is generally considered to indicate near depletion of additives, and is a safe point to change your oil. Once the additives are depleted then the infamous sludge that the crazy Scot from the Castrol commercials has been warning us about can begin to form. A virgin sample of the identical oil that I used here (Pennzoil Ultra 5w30) begins with a TBN of 11.7.

TAN

The TAN (Total Acid Number) is the amount of potassium hydroxide measured in milligrams needed to neutralize the acids in one gram of oil. When plotted on a graph with the TBN, the point at which the two lines cross is the optimal point to change your oil and indicates nearing additive depletion. For cost reasons I didn’t get the TAN test done because the TBN is a more reliable method to determine the active additive remaining.

- Stark, J. (n.d.). Spectrometry: The Marvel Of The Lab. Retrieved April 6, 2011, from Blackstone Labs:

- What Is Oil Analysis? (n.d.). Retrieved April 6, 2011, from Bob Is The Oil Guy: Link

- Sources Of Wear Metals In Oil Analysis. (n.d.). Retrieved April 6, 2011, from Bently Tribology Services: